| | PAGE 1/A SECTION |

TODAY o January 21, 2001

|

|

Palestinians don't want to give up 'right of return'

Saeed Ahmed - Staff

Sunday, January 21, 2001

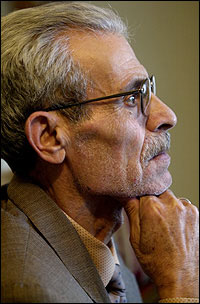

Saber Ayoub was 23, newly married and about to take over the family farm when his family was forced out of the village of Safad in northern Palestine by advancing Israeli troops. He thought the family would return in a week or two.

Fifty-three years later, Ayoub is still waiting.

Now a frail 76, the Palestinian exile, who settled in Atlanta in 1989 after decades in refugee camps in Lebanon, still speaks longingly of his family home --- where the vineyards produced the sweetest grapes and wildflowers cast the hills in a brilliant yellow.

His desire to return has never wavered, even as the 150 acres of land that once constituted his farm has given way to Jewish settlements.

"I have moved from place to place, stateless, all my life, and all I ask for is a graveyard in the land that I call home," says Ayoub, the tears welling in his eyes, "but even that has become a political issue."

And so it goes for the nearly 4 million Palestinian refugees, whose families fled or were driven from their homes during Israel's 1948 war of independence and subsequent fighting. Hundreds settled in metro Atlanta, but the exact number is difficult to come by. Most had to assume the citizenship of another country as Palestine is not officially recognized as a nation.

Some carry rusty keys to homes destroyed long ago, others yellowed land deeds or faded photographs.

As Israeli and Palestinian diplomats try to hammer out a peace deal, the fate of these refugees is proving to be one of the biggest obstacles.

To such displaced Palestinians, sovereignty over the disputed Jerusalem shrine the Muslims call Haram Al-Sharif means nothing if they have to trade away their "right of return."

"That's like spitting in our faces," says Ayoub's son Nabil. "The Israeli position on the refugee situation has been that 'the old will die and the young will forget,' but the names of our towns and where we belong has been fed to us with the milk our mothers nursed us with."

While Palestinians say their right to return is well-grounded in international law --- they cite the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Fourth Geneva Convention and United Nations Resolution 194, which mandates that refugees wishing to return to their homes be permitted to do so --- Israel has resisted.

To Israelis, opening the door to all Palestinian refugees would not only place an unbearable economic strain on their country but would result in what Israel calls "demographic suicide."

Israelis fear an influx of Palestinians would dilute the Jewish character of Israel and, with the country's population already 20 percent Arab, relegate the 5 million Jews to minority status.

"The very nature of the state of Israel is in jeopardy if all Palestinian refugees are given an unlimited ability to live in Israel," says Kenneth Stein, professor of Middle Eastern history at Emory University.

But Hussein Ibish, communications director of the American-Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee, says the refugees have a fundamental right that ought to be granted.

"The rights of refugees is one that is upheld so vociferously by the international community that we even went to war with Yugoslavia, a sovereign state," says Ibish. "We didn't buy into Serbia's ethno-national ambition, but somehow in this instance, we find this argument compelling."

The Palestinian refugee crisis has had as many phases as Israel has had wars. About 700,000 Palestinians fled in 1948, and more waves of refugees followed the 1967 and 1973 Arab-Israeli conflicts.

Today, Palestinians constitute the largest refugee population in the world --- one in every four refugees is a Palestinian. About one-third live in 59 U.N.-supported camps around the Middle East.

Among those living in the worst conditions are the 370,000 refugees marooned in Lebanon, where Ayoub lived for 41 years before moving to the United States.

Because the Lebanese government didn't want the refugees upsetting the nation's fragile ethnic mix, it restricted their interaction by denying them all but the most menial jobs and barring them from all social services.

Ayoub managed to save enough to open a grocery store in Beirut and things were beginning to look up --- until the 1982 massacre in Shatila, the camp in which he lived.

Following the assassination of Lebanese President Bashir Gemayel, members of the South Lebanon Army --- vowing to avenge his death --- slaughtered 7,000 civilians in a 36-hour rampage in Shatila and a second camp, Sabra.

The Ayoub family escaped unharmed, and soon after, Ayoub's eldest son, Nabil, made his way to America, graduated from college and landed a job as a software engineer. The father followed in 1989.

Now sitting in a friend's house in south Cobb, Ayoub swaps stories with other refugee families.They spin romantic tales about the land they left behind a half-century ago, and console one another on their shared plight.

His son Nabil is now 33 and has never set foot in his hometown. But he remembers it well, he says, from treks to the Israeli-Lebanese border where his father would point out their property and regale him with stories of life on the farm.

Unlike his father, Nabil Ayoub's emphasis is on the "right" more than on an actual "return" to Palestine. He doesn't want to live under Israeli sovereignty now that he has made a life for himself in another land, he says.

But still, he insists, he ought to be given that option.

"Until that dream is reached, I will pass on to my child the dream my father has willed to me," says the younger Ayoub, who will become a father himself this year.

To this, the grandfather-to-be chimes in, "When my grandchild is born and learns to speak, one of the first words I will teach her is 'sanaoud, sanaoud' " -- Arabic for 'we will return, we will return.'

See what reader had to say about this story See what reader had to say about this story

|